Under the Radar

The Book of Genesis asked countless generations “how did we get here?” But by now it also asks, “how did IT get here?”

An Egyptian clerk in a liquor store once assured me that the stories of the early Bible were some early versions of comic book superheroes. Exhibiting the cockiness of a man who knows that those early Pharaohs were building pyramids some 2000 years before the earliest extant remnant of Pentateuch has been dated, the cockiness of a man whose tribe was leaving written records 2000 years before the earliest Hebrew fragments, he listed a few Pentateuch miracles and insisted they could be as easily ascribed to Superman or Green Lantern as to Moses.

With him in mind, I decided to make the book of Genesis my first comp lit reading excursion this year. The Book of Genesis! Hasn't everyone read it?

I doubt it.

I was not bored; in fact, an astonishing amount of it was completely unfamiliar. In fact, barely five – of fifty – chapters in, I was thinking, "Wow, I'll bet not many have read this thing start to finish." The first surprise is simply how long it is. Genesis – Hebrew name בְּרֵאשִׁית – is about 32,000 words. It easily weighs in at novella length. Easily. In fact, it's over five percent longer than "Of Mice and Men" and "Double Indemnity" and over ten percent longer than "A Christmas Carol" and "Breakfast at Tiffany's."

But that's a mere bagatelle compared to the larger surprise: what an outrageous, lewd, cunning, frank, and often sinister assemblage it is. I referred to commentary many times while reading it. Here are some examples you may not recall: Abram has relations with a handmaiden; it's his wife's idea. Jacob, he who wrestled with the angel, will father children through four different women. A local chieftain wants to marry Jacob's daughter Dinah, and Jacob's tribe insists that his whole rival tribe be circumcised as a condition of the betrothal; then, while that tribe is recovering from the impromptu surgeries, Jacob's tribe slays them all. And, maybe most lamentably, the impetus for the flood is that "The Lord regretted that he made men on earth." Almost forgot: that Patriarch of Patriarch, Abram, passes Sarah off as his sister to curry better favor. (But the Lord gets upset not with Abram but with Pharaoh, for fancying her.)

Other oddities: the Ark is made of gopherwood. What is gopherwood? Nobody knows. Oh, and there's my favorite snicker of all: when God destroys Sodom, he sends two angels, whom Lot takes care of. The angels decide to pass the night in Lot's own home. The town hears that there are hot men in Lot's home, and they're ready to get to them. Lot begs them not to. "Stand back!" they jeer at him. "We'll treat you worse than we'll treat them!" These are men ready for business. Really – this is Genesis 19.

So where does the "inspired" part come in? I can't tell you the cases for divine inspiration that the ancient sages and the saints have made; why would I dare to paraphrase such arguments? God hits you with them, if you're interested. But as an editor I can tell you the case for my own contemporary awe, which is wrapped up in all modernity you can stand to bring to this book. My awe is for the transmission of the stories, and especially for their transmission in captivity.

The Sumerians wrote on clay tablets. The Egyptians had stone and also papyrus. The Greeks at Pergamon were turning animal skin into parchment. Those Hebrews, the Canaanites . . . they had sheep. And they were often in the captivity of another nation.

We can draw some idea of what it’s like to write in captivity from a podcast called “Subversive Orthodoxy.” Here’s a transcription of author (and friend of the press) Robert Inchausti on Alexander Solzynitzhen’s clandestine process:

https://feeds.buzzsprout.com/2443460.rss

The name itself invokes for me those two months that I dedicated to reading Solzynitzhen and realizing that I would say every review I read of it was written by somebody who hadn't read the book. Because you could only say these glib one-liners if you hadn't been with the guy through his arrest, through his torture, through his interrogations, in his marching on the tundra, trying to write without a pencil. The way he writes without a pencil is, you memorize your lines while you're marching on the tundra, and you make every fifth line rhyme. So if the fifth line doesn't rhyme, you forgot a line. So now you have to continue marching to find that line that you dropped. And then, once you pick it up again, then you're allowed to go onto the next. And he did this for months. So when he finally gets access to a pencil, he has to bury it in his cell because it's contraband, and he can't let anyone see that he has a pencil. And then, when he finally gets a piece of paper, five months later, he has to cut it in little strips, and bury it in little rolls in his cell. And then, when he decides to write, he doesn't want to waste the paper, so he develops a script that contains no vowels, so he can just write with consonants that will bring back to him these precious descriptions and points he wants to preserve, never knowing if he'll ever be able to dig them up from his cell and be able to send them in letters or however he's going to get them out. That's still up to question. And even if he got them out, they would never be published in the Soviet Union, because the censors would never allow any stories about the Gulag, because it didn't exist. So, when he finally gets out, and I know we're going ahead of the story, he decides that now he's going to be able to write. When they arrested him, they asked him what his occupation was; he had been an officer in the Russian Army in WWII. He was sent from the front in WWII to the Gulag. So he went from fighting the Nazis to being the victim of his own government. He wrote that his profession was "atomic scientist." He wasn't an atomic scientist, but he thought that they would be less likely to kill an atomic scientist.

Thanks for that, professor. Scholars have had trouble dating a single shred of the composition of Genesis, which ironically labors so much to be a reliable chronology, to any particular century. But they are entirely confident that the whole Pentateuch existed at least a few centuries before its earliest known fragments. The various states of captivity of the various tribes of Israel must account for at least some of this diachronism; if we can bear witness to the trouble pencil-pushing Solzhynetisin had composing his own book, we can only imagine how much trouble people often without paper, papyrus, clay tablets, or parchment had in anchoring any part of the Pentateuch. This much alone, to me, is the miracle: that it survived at all.

The long story of Joseph that concludes Genesis represents a departure from the far briefer, picaresque adventures found in the rest of the holy book. The sustained, complicated narrative of the Joseph chapters, in which facts must be held in imagination for climactic or ironic effects hundreds of verses later, has been called a "wisdom novella," detouring only in the second chapter in the sequence, which provides a couple of sexual excursions (cf. Onan, eponym of onanism, and a call-me-maybe temple prostitute episode.)

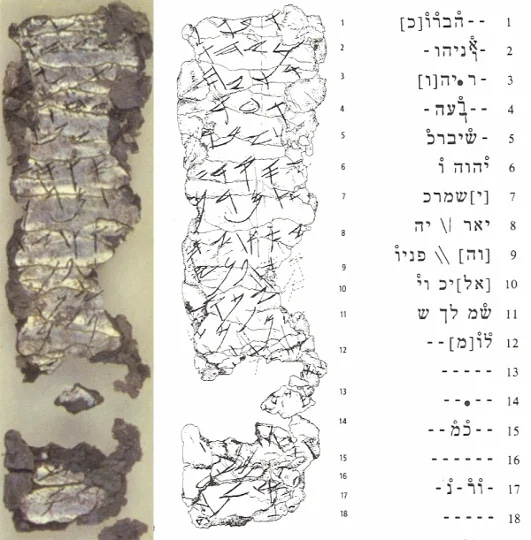

I always sat up with special attention to the story of Joseph in Sunday School, because not only was Joseph my own name, and not only was it my father's name, but my father was, like Joseph, the youngest of twelve – assuring that that level of ironic wit might endure in this particular tribe for a couple of generations. Now I sit up with special attention to learn, for instance, that the earliest known Hebrew fragment of the Pentateuch is not precisely on a scroll but on an amulet: the so-called Ketef Hinnom scrolls, found in 1979. These fragments of a verse from Numbers are a full 1600 years earlier than the text typically used for modern translations of the Pentateuch, the Codex Leningradensis, the oldest known complete Hebrew bible. (They're still arguing in theological seminaries and on Reddit whether Jerome's Hebrew Masoretic text is better than the Greek Septuagint so familiar to Augustine, and of course whether the Deuterocanonical works in the Dead Sea Scrolls favor one over the other, but let's just let them continue to have at it.)

In the end, the whole case for an unusual text like Genesis being authoritative and holy is the same case I recall John of the Cross making to an acolyte one day while reading a Bible under a tree. A miracle-worker was coming to town and the acolyte asked John if he was going to go bear witness to the man and his work. "No," John said wearily, "I have all the miracles I need right here."

I often feel the same way when visiting a liquor store and striking up surprising conversations. Take it or leave it, Egyptian pal of mine.

I never thought I'd be so enchanted by a commentary on Genesis, which I only read from my youth Bible gifted to me at my age 7 first communion. And many thanks to Mr. Inchausti's taste of Solzhenitzen's ordeal.